News

Interview with Dr Hubert BALIQUE, senior lecturer in public health in Marseilles

We recently met Dr. Hubert Balique, a senior lecturer in public health in Marseilles, who is committed to international humanitarian action. In collaboration with Santé Sud, he was one of the first to set up field medicine in Mali. We asked him about his experience and his vision of the medicalization of rural areas.

Dr. Hubert Balique has been working in Mali since 1975, when he first set up teams of community health workers at village level. From 1989 onwards, he was instrumental in setting up the first country doctors to meet the needs of rural populations, thereby strengthening their access to primary care.

In this article, he describes the CSCOM (community health center) model, based on a multidisciplinary team led for the most part by a medical doctor, and community management. To ensure the viability of these centers, he stresses the importance of contractualized balancing subsidies, certification and integration into national health policy.

Can you tell us a little about your background and what led you to work on the medicalization of rural areas, particularly in Mali?

Dr. Hubert Balique: My career path began in Marseille, where I studied medicine, after which I decided to get involved in international humanitarian action. I was a doctor in Bangladesh with Médecins Sans Frontières in 1972, then in a refugee camp in Vietnam during the American war, with the Red Cross, in 1973.

After specializing in public health, I left for Mali in 1975 to carry out my civic service as a teacher at the Bamako Faculty of Medicine. With the agreement of the Dean, I moved to a rural area where I set up a “rural health training and research center”, where I taught for many years and supervised numerous theses and dissertations.

One of my first initiatives was to organize, from 1976 to 1983, the training and follow-up of community health workers to promote primary health care in the villages of the health districts.

I then worked in Bamako as Regional Health Advisor for the Coopération Française in the embassies of Mali, Senegal, Burkina and Niger, before continuing my professional involvement with the Coopération Française, ORSTOM (now IRD), the European Union and the AFD, while undertaking short-term missions in a dozen sub-Saharan African countries at the request of organizations such as the World Bank, the European Union and the WHO. In addition to my duties as a teacher-researcher, I also held the position of Technical Advisor to the Ministries of Health in Mali and Niger, and managed health development projects in the interior of the country.

This cumulative experience has enabled me to consolidate my vision of healthcare systems in Sahelian countries and to reinforce my conviction that, 45 years after the Alma Ata conference, the medicalization of rural areas is essential today.

I would like to point out that, in 1974, Mali only had around a hundred national medical doctors, whereas today it has between 10,000 and 15,000, that almost 300 new Malian doctors are trained every year in Bamako and, above all, that today’s priority must be to improve the quality of care.

How did your perception of the issues involved in medicalizing rural areas evolve during this period?

Dr. Hubert Balique: In 1982, an agreement between the Malian government, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank led to the signing of a Structural Adjustment Program designed to stabilize public finances by reducing budget deficits, which were spiraling out of control. In 1985, this led to an end to the systematic employment of new graduates from training institutions and the introduction of an entrance examination for the civil service, drastically limiting the number of budgetary posts. However, to compensate for these restrictions, private practice of the healthcare professions was authorized, thus ending the state’s monopoly on the healthcare sector and opening the way to new strategic options in the healthcare field.

The results of my many years of public health practice in the field, enlightened by my missions in other Sub-Saharan African countries and by numerous research works and evaluation reports on the subject, led me to identify the limits of community health workers, as well as the conditions for their effectiveness and sustainability. With a view to helping medical students enter the world of work after graduating, I was instrumental in setting up the first community health centers in Bamako, then in rural areas, which helped to boost the performance of the national health system in meeting the needs of the 75% of the population living in rural areas.

A meeting of graduating students, organized at the Faculty of Medicine in 1988 in the presence of the Director of Santé Sud, to encourage new graduates to practise their profession in rural areas, led to the installation of the first field doctor in 1989, then to their multiplication over the following years until the number of field doctors in Mali exceeded 200.

Whether in villages or peri-urban neighborhoods, CSCOM doctors are unique in that they practice their profession outside the civil service, while meeting the requirements of the public health service, in a manner that is typical of the social and solidarity economy.

Contrary to the assumption that African doctors refuse to settle outside the cities, and that rural populations are too poor to contribute to the financing of their care, the setting up of rural doctors in Mali has shown that a significant proportion of the continent’s young medical doctors are prepared to live in villages to practise their profession for several years (some have remained there until retirement), provided that they can find minimal conditions of welcome from a professional and family point of view, the provision of suitable accommodation being a requirement.

They have also shown that, when the fees charged are commensurate with their purchasing power, the majority of the population living in rural areas is able to ensure the financial viability of these centers, provided that the quality of care is assured, and that country doctors are consequently able to generate sufficient income from their practice.

The roles played by the Bamako Faculty of Medicine and Santé Sud over all these years have been essential in consolidating these facilities by improving the quality of their care and their impact, while ensuring their sustainability. The role played by Santé Sud teams in France and Mali has been decisive, through the regular technical support missions of their doctors in the field, the continuity of the partnerships set up between French and Malian field doctors, and their financial support.

Could you describe the ideal operating model for a community health center?

Dr. Hubert Balique: Community health centers, or CSCOMs, are private, not-for-profit health structures that provide front-line curative, preventive and promotional care in health sectors with around 10,000 inhabitants in rural areas and 20,000 in urban areas. They are administered by a community health association, or ASACO, which is open to the entire population of the sector, giving the center its legal personality and constituting a privileged tool for citizen participation in improving their health and that of their families. The 35 years of existence of these centers have enabled us to place particular emphasis on 7 essential points to guarantee their effectiveness and sustainability.

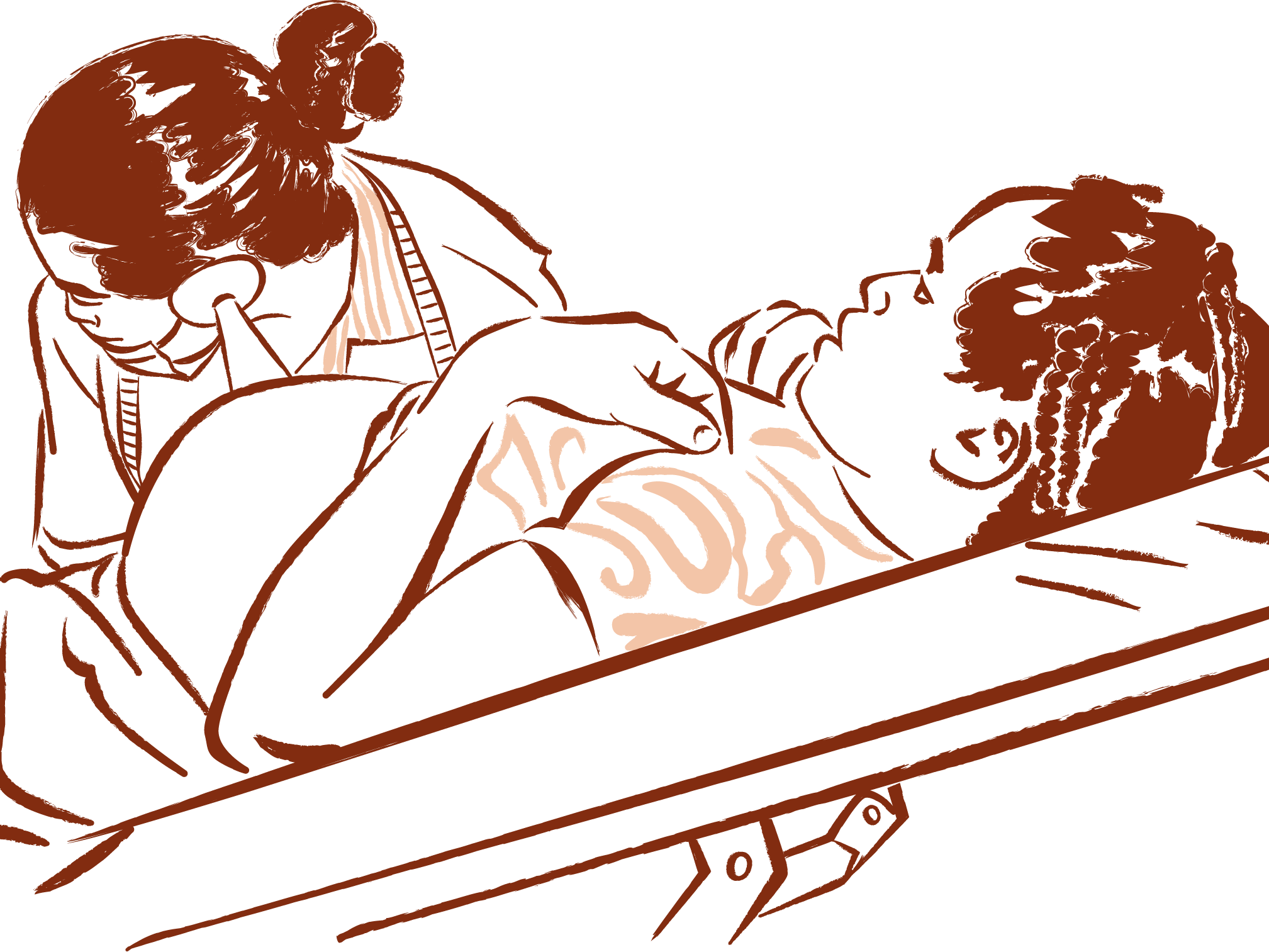

- To fulfill its mission, a ComHC in a rural area needs a team of at least 9 people, including 1 doctor, 2 nurses, 2 midwives (or, failing that, nurses trained in obstetrics), 2 health auxiliaries, 1 manager-pharmacist and 1 caretaker-labourer. The members of this team must sign a private law contract with the ASACO and adhere to a collective agreement specific to their profession. They must also benefit from a profit-sharing scheme, which must be significant enough to motivate these healthcare professionals.

- This team must provide the full range of services laid down by the Ministry of Health, from first-line curative care to preventive and promotional care, distinguishing between fixed activities at the health center and advanced activities through regular motorcycle trips to the villages in the health sector.

- The supply of drinking water to the centers must be guaranteed, and new technologies such as solar energy, computerization and Internet access, linked to the national digitized health information network, must be appropriately installed.

- All patients treated by the center must benefit from the permanent availability of essential pharmaceutical products presented under their international non-proprietary names.

- The center must operate within the framework of a public service delegation, based on the signature of a permanent agreement between the center’s medical director, the president of its ASACO and the district medical director, representing the State, which must be implemented through annual contracts specifying the activities to be carried out and their financial implications. The latter must determine, using activity simulation software and accounts drawn up for this purpose, the forecast operating deficit to be covered by the subsidy granted to each center, so that it achieves the essential balancing of its accounts according to its results.

- All centers must be regulated in such a way as to give priority to improving the quality of the care they provide and controlling their unit production costs, through the introduction of a certification mechanism.

- Country doctors must organize their continuing training collegially through their professional association, with pedagogical support from medical school teachers and Santé Sud practitioners.

What is your vision for the future of physician training, particularly in the context of rural medicine?

Dr. Hubert Balique: If the initial training of Malian doctors is to meet the needs of the healthcare system as effectively as possible, it must adopt as its teaching profile the functions and tasks of the country doctor, as a medical practitioner in a remote post, as the technical director of a CSCOM and as a public health manager.

Practising at a distance from a hospital and practising the specifics of their profession means that a competent country doctor can easily practise general medicine in the city, whereas the reverse is not true. The only solution has been to set up a university diploma that includes work placements with rural doctors recognised as training supervisors, with the support of Santé Sud and the Association Malienne des Médecins de Campagne (Malian Association of Rural Doctors), which also organises regular meetings for the continuing education of its members and for exchanges between professionals.

How can we ensure the economic viability and sustainability of community health centres?

Dr. Hubert Balique: To ensure the success of ComHCs, it is essential to integrate them into the economic model of the country’s health policy. Mali currently spends around US$700 million a year on the health sector (or US$35/person/year, compared with US$5,200 in France) and its public spending on health represents 6% of its national budget, well below the 15% recommended by the WHO in Abuja in 2021. To ensure that the ComHCs function properly, guaranteeing the quality and sustainability of care and meeting public health objectives, they need to break even each year. To achieve this, the centres must receive funding from the State, supplemented by its technical and financial partners (TFPs), in order to provide each of them with a balancing subsidy to cover all the costs of the public health service. The creation and management of a common fund will enable all these financial contributions from the State and its partners to be pooled.

These balancing subsidies must be included in the public service contracts signed between the health centre and the State, which must be subject to periodic assessments of the activities carried out, their impact and their accounts.

The expenditure taken into account must include both fixed costs (staff remuneration, maintenance, depreciation of equipment, etc.) and variable costs (pharmaceutical products, travel, communication, etc.). The income of these centres will come from direct payments from patients or indirect payments via the Universal Health Insurance Scheme, the funding of public health activities and balancing subsidies.

The future financing of health policy, and therefore of the ComHCs, is based on the development of the Universal Health Insurance Scheme, with its four components: compulsory health insurance (AMO) for the formal sector, mutual health insurance schemes for the informal sector, the Medical Assistance Scheme (RAMED) for the poor and a future fund for legal free services (pregnancy, childbirth, children under 5, certain social diseases such as AIDS, tuberculosis, sickle cell anaemia, type 1 diabetes, etc.).

Without waiting for all these measures to be implemented at national level, they must be integrated at local level as part of projects to support the strengthening of health systems, in which NGOs in particular are involved.

Find out more

Testimony of Tarek GRIRA, Project Manager of the Sa7et Al Mojtama3 programme

Petite Terre